“Trauma is not what happens to you, it is what happens inside you, as a result of what happens to you.” Dr Gabor Maté

What is EMDR?

It has been almost 36 years since Eye Movement Desensitisation and Reprocessing (EMDR) was first discovered and developed by Dr Francine Shapiro, an American Psychologist. A by chance discovery has now established itself as an evidence-based psychotherapy helping children, young people and adults to recover from the symptoms of emotional distress caused by experiencing negative adverse or traumatic life events (Shapiro, 2018). EMDR is now widely recognised and accepted by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) and the World Health Organisation as an effective treatment for children and adolescents struggling with mental health. We are passionate about using EMDR with children and young people given its least intrusive therapeutic approach and its ability to achieve positive results quickly when compared with other types of therapy (Mavranezouli et al. 2020). Children are not obliged to trawl at length through their trauma narrative which relies on adequate language skills and their ability to tolerate talking about their distress.

How does EMDR work?

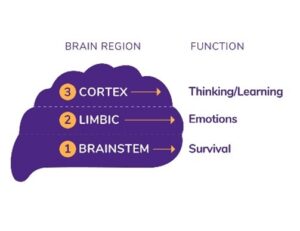

Speaking at a conference in 2016, Dr Bruce Perry, a child and adolescent psychiatrist, commented that despite many scientific advancements over the past 50 years, we are only just scratching the surface in terms of what we know and understand about the human brain. However, what we do know is that our brains develop from the bottom up, with the brain stem being the first structure to be established, followed by the limbic system and finally the cortex. We also know that the brain has a natural healing mechanism that can help us recover from experiencing stressful or traumatic events. When our brains function effectively, the memories, body sensations and thoughts associated with these events are processed and are stored in neural networks. This allows us to remember the key information about the stressful event, but it does not cause us to experience emotional pain or distress on an ongoing basis. Much of this processing is thought to be done when we are in a specific state of sleep known as rapid eye movement (REM) sleep. Often worries or distress felt after a quality night’s sleep can seem less significant and emotionally charged than the day before.

As with any organ in our bodies, our brain and nervous system can become overwhelmed if the experience of the event is deemed too demanding or if it has happened repeatedly over time. What we think happens, is the information associated to the overwhelming experience, becomes stuck in an isolated neural network which the brain is not able to access and process. When the memories, body sensations and thoughts associated to the event are left unprocessed we are likely to experience ongoing emotional pain or distress often triggered by our current environment. With children, the symptoms of this distress can appear as flashbacks, nightmares, problems sleeping, avoiding social events/school, panic attacks, poor attention/focus, poor educational achievement, anxiety, depression, poor self-esteem, poor emotional regulation, difficulty with relationships and behaviour, obsessive & compulsive thoughts or negative physical sensations. Trauma is not only relevant to those who have experienced war or sexual abuse. Many day-to-day small experiences can produce a stress response in the body and result in unprocessed information. This is especially true for children and young people who must cope with a lot of change in their daily lives at a point when their brains are are not fully developed.

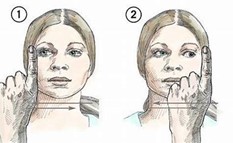

EMDR works by helping our brains and nervous system digest and reprocess experiences that have become stuck and are the cause of emotional pain and distress. Through reprocessing and desensitising these experiences and thus altering the neural circuity of the brain, the level of emotional distress associated to the event may be reduced or released all together. The key technique EMDR uses to aid the brain’s natural healing process is called alternating bilateral stimulation (ABLS). ABLS can be done by asking the child to move their eyes from left to right, holding hand buzzers or self-tapping/movement while asking them to think of the event causing them distress or discomfort. Parents often report that following EMDR, their child may still recall the event, yet they no longer have negative, distressing emotions or sensations related to it or their perception of the event has positively changed. They can be informed of the memory or trigger without being controlled by it.

Who is EMDR appropriate for?

Because each child or young person is uniquely different, based on the genetics they were born with and the life experiences that shape them, distressing or traumatic experiences will impact them in unique ways. Although many young people can process and cope well with life challenges or traumatic experiences others may need more support. If your child or teen is struggling with feelings of any kind of emotional distress which is having an impact on their quality of life, we are always ready to listen and try to help. The criteria for therapy is wide ranging and a young person does not have to endure severe trauma or be diagnosed with post-traumatic stress to benefit from therapy. One trauma cannot be compared to another, and even seemingly mild traumatic events that occur cumulatively over many years can produce a significant trauma response in the body.

What will the therapist ask me to do?

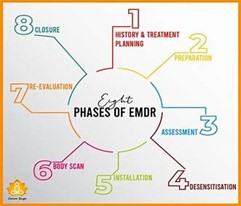

The therapy is child-centered, which means it progresses at the pace that the young person needs and can tolerate. The EMDR eight phase model includes history taking, preparation, assessment, processing/desensitisation, installation, body scan, closure and reevaluation. In real terms this means that the first few sessions will focus on gathering a detailed history of their development and life experiences to make links between past events and current day triggers – this informs a bespoke therapy plan and helps the child understand why they are struggling. Emotional regulation techniques are next taught and modelled with the child before preparing them for desensitisation. Each session is clearly explained to the young person with a focus on psychological safety and regulation before processing any distressing material. Psychoeducation about the symptoms of distress is explored with the child with a focus on where and how this feels in their body. EMDR processing sessions usually take less time and the young person will be asked to talk, draw/create or keep in mind the distressing target that they want to work on. What they share in the therapy space is entirely up to them and they feel fully in control of this process. Children will respond much better to intervention when they feel they have a sense of control over it rather than something that’s being done to them. Unlike CBT there is no homework tasks to be completed between session. As with any therapeutic intervention the key part of its success relies on the therapeutic relationship being established where safety, trust and validation are essential.

How many sessions will I need?

Following the initial preparation sessions some young people may only require a few processing sessions to help resolve their distress, whilst others will require longer term intervention, especially if their circumstances are more complex. NICE guidelines suggest that EMDR with adults can be delivered over 8-12 sessions. Although, it is generally recognised that children and young people will typically process quicker due to having less life experience to work on.

How long do the sessions last?

Sessions last between 60-90 minutes.

What if the distressing event occurred before my child could talk?

Even preverbal experiences can be worked on through EMDR. Just because a young person experiences a disturbing event at a preverbal stage and hence may not have the cognitive recollection of these memories, the event may still have had a physical impact in their bodies which can then be worked on through therapy. It is also possible to work on current triggers linked to preverbal memories to help access this trauma and reprocess it.

Will my child have to talk in great detail about their experiences during the sessions?

For most young people under 16 years the therapist will want to discuss their developmental history and life experiences with the parent first. This way the therapist will already have a good knowledge base about the young person before they meet them. The young person will feel in control in terms of how much information they want to share with the therapist. In fact, during processing sessions the less information the young person provides the better. Adaptations can be made so they need not talk at all or they may be encouraged to us

e art/play techniques if communication is difficult. Ensuring adequate time is given to developing a positive therapeutic relationship is so important to help encourage the child or young person to feel safe in sharing their experience.

Is EMDR effective for children with neurodiversity?

EMDR can be effective for young people with a range of diagnosed conditions for example autism spectrum, attention d

eficit hyperactivity and or learning differences. Adaptations can be made to the treatment to ensure young people are able

to access therapy in the most effective way e.g. play, sensory and narrative story telling techniques.

Can sessions be done face to face or online?

Depending on the young person’s needs and wishes sessions can be delivered either online or fac

e to face.

“Traumatized people chronically feel unsafe inside their bodies: The past is alive in the form of gnawing interior discomfort. Their bodies are constantly bombarded by visceral warning signs, and, in an attempt to control these processes, they often become experts at ignoring their gut feelings and in numbing awareness of what is played out inside. They learn to hide from their selves.”

Dr. Van Der Kolk